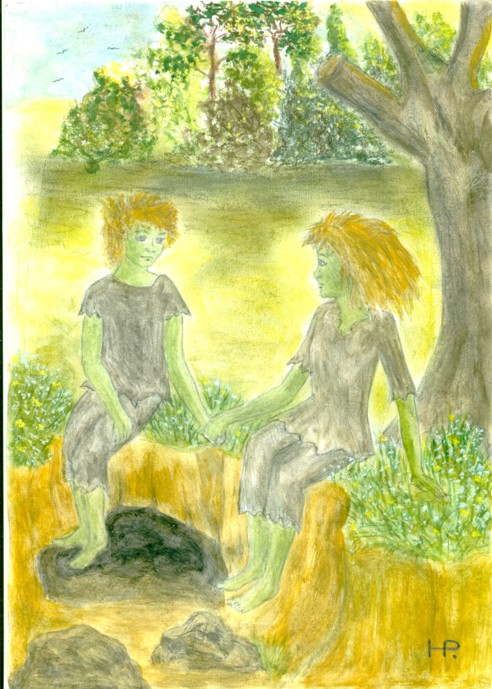

12th Century Legend of the Green Children of Woolpit , Suffolk, UK

The legend of the green children of Woolpit

concerns two children of unusual skin colour who reportedly appeared in

the village of Wool Pit in Suffolk, England, some time in the 12th

century, perhaps during the reign of King Stephen. The children,

brother and sister, were of generally normal appearance except for the

green colour of their skin. They spoke in an unknown language, and the

only food they would eat was beans. Eventually they learned to eat

other

food and lost their green pallor, but the boy was sickly and died

soon after he and his sister were baptised. The girl adjusted to her

new life, but she was considered to be "rather loose and wanton in her

conduct". After she learned to speak English, the girl explained that

she and her brother had come from St Martin's Land, an underground

world whose inhabitants are green.

One day at harvest time, according to William of Newburgh during the

reign of King Stephen (1135–1154), the

villagers of Woolpit discovered two children, a brother and sister,

beside one

of the wolf pits that gave the village its name. Their

skin was green, they spoke an unknown language, and their clothing was

unfamiliar. Ralph reports that the children were taken to the home of

Richard de Calne. Ralph and William agree that the pair refused all

food for several days until they came across some raw beans, which they

consumed eagerly. The

children gradually adapted to normal food and in time lost their green

colour. The boy, who appeared to be the younger of the two, became

sickly and died shortly after he and his sister were baptised.

After

learning to speak English, the children – Ralph says just the

surviving girl – explained that they came from a land where the

sun never shone and the light was like twilight. William says

the

children called their home St Martin's Land; Ralph adds that everything

there was green. According to William, the children were unable to

account for their arrival in Woolpit; they had been herding their

father's cattle when they heard a loud noise (according to William, the

bells

of Bury St Edmunds and

suddenly found themselves by the wolf pit where they were found. Ralph

says that they had become lost when they followed the cattle into a

cave and, after

being guided by the sound of bells, eventually emerged

into our land.

According to Ralph, the girl was employed for many

years as a servant in Richard de Calne's household, where she was

considered to be "very wanton and impudent". William says that she

eventually married a man from King's Lynn, about 40 miles (64 km)

from Woolpit, where she

was still living shortly before he wrote. Based

on his research into Richard de Calne's family

history, the astronomer

and writer Duncan Lunan has concluded that the girl was given the

name "Agnes" and that she married a royal official named Richard

Barre.

The only near-contemporary accounts are contained in William of Newburgh's Historia rerum Anglicarum and Ralph of Coggeshall's Chronicum Anglicanum, written in about 1189 and 1220 respectively. Between then and their rediscovery in the mid-19th century, the green children seem to surface only in a passing mention in William Camden's Britannia in 1586, and in Bishop Francis Godwin's fantastical The Man in the Moone, in both of which William of Newburgh's account is cited.

Two

approaches have dominated explanations of the story of the green

children: that it is a

folk tale describing an imaginary encounter with

the inhabitants of another world, perhaps one beneath our feet or even

extraterrestrial, or it is a garbled account of a historical event.

The

story was praised as an ideal fantasy by the English anarchist poet and

critic Herbert Read

in his English Prose Style, published in 1931. It

provided the inspiration for his only novel, The Green Child written in

1934.

Our Lady of Woolpit:

Until the Reformation the church housed a richly adorned statue of the Virgin Mary known as

"Our Lady of Woolpit", which was an object of veneration and

pilgrimage, perhaps as early as about 1211. There is a clear indication

of the existence of an image of the Virgin in a mid-15th century will

that speaks of "tabernaculum beate Mariae de novo faciendo" ("in making

new/anew the tabernacle of Blessed Mary"), which sounds at least like a

canopy or even a chapel for housing an image. It stood in its own

chapel within the church. No trace of the chapel survives, but it may

have been situated at the east end of the south aisle, or more probably

on the north side of the chancel in the area now occupied by the

19th-century vestry.

Pilgrimage to Our Lady of Woolpit seems to have been particularly

popular in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and the shrine was

visited twice by King Henry VI, in 1448 and 1449.

In 1481 John, Lord Howard (from 1483 created Duke of Norfolk by Richard

III), left a massive £7 9s as an offering for the shrine. After the

Tudor dynasty had consolidated its hold on the English throne, Henry

VII's queen, Elizabeth of York, made a donation in 1502 of 20d to the

shrine.

The statue was removed or destroyed after 1538, when Henry VIII ordered

the taking down of "feigned images abused with Pilgrimages and

Offerings" throughout England; the chapel was demolished in 1551, on a

warrant from the Court of Augmentations.

The Lady's Well of Woolpit:

In a field about 300 yards north-east of the church there is a small

irregular moated enclosure of unknown date, largely covered by trees

and bushes and now a nature reserve. The moat is partially filled by

water rising from a natural spring, protected by modern brickwork, on

the south side; the moated site and the spring constitute a scheduled

ancient monument.

The spring is known as the Lady's Well or Lady Well. Although there are

earlier references to a well or spring, it is first named as "Our Ladys

Well" in a document dated between 1573 and 1576, referring to a

manorial court meeting in 1557–58.[9] The name suggests that it was

once a holy well dedicated like the church and statue to the Virgin

Mary, and it has been suggested that the well itself was a place of

medieval pilgrimage.[16] There is no evidence to suggest that there was

ever a building at the site of the well, or even to support the

claim of its being a specific goal of pilgrimage. In fact the well was

on land held not by the parish church but by the chapel of St John at

Palgrave.

At some unknown point, a local tradition arose that the waters of the

spring had healing properties. A writer in 1827 described the Lady's

Well as a perpetual spring about two feet deep of beautifully clear

water, and so cold that a hand immersed in it is very soon benumbed. It

is used occasionally for the immersion of weakly children, and much

resorted to by persons of weak eyes. Analysis of the water in the 1970s

showed that it has a high sulphate content, which may have been of some

benefit in the treatment of eye infections.

Source: Wikipedia

Illustration by Hilary Porter