Britannia Obscura: Mapping Hidden Britain by Joanne Parker

Horatio Clare delights in a tour of Britain’s hidden byways, following in the footsteps of cavers and ley-line hunters, balloonists and Druids

'What shape is Britain?” Joanne Parker asks in this gently inspiring book about ways of seeing and mapping various hidden parts of Britain, traced through cave systems, along skyways, via ley lines and canals. Her answers include a wingless dragon and a bob-tailed dog. I see a slightly mad old man, leaping off the continent, varicosely-veined with motorways, but reading Britannia Obscura greatly expands one’s vision.

The Britain you see, Parker discovers, depends on your pastimes.

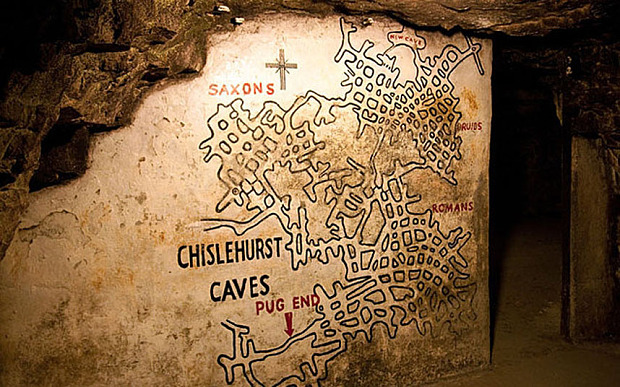

For 8,000 Druids the nation is a network of megaliths, standing stones and circles. (If that sounds like a lot of modern mistletoe mystics, in 1831 the Ancient Order of Druids had 200,000 members.) For 20,000 cavers there is almost no east or South East England: their map is a stitching of tunnels and caverns running from the West Country through Wales and the Peak District into the north. Their weekends are spent amid “grand stalagmites, intricate helictites and aragonite needles, gypsum crystals and crystal pools”, according to caver Tarquin Wilton-Jones.

There are 1,800 kilometres of British caves, but that is not enough for the Wilton-Jones ilk, who spend much time digging, clearing rockfalls and unblocking passages; “a small but determined mud-spattered army”, as Parker describes them, “chipping away in search of that vast, pristine chasm that must – really must – exist in one of those blank, empty spaces on the map of underground Britain”.

Parker’s tour is conducted with a light touch in prose which makes learning from her a pleasure. She makes delightful connections between eras and activities, and is conscious of the value of the unknown and uncertain in our lives. I had no idea that Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed Box Tunnel on the Great Western Railway so that the rising sun would shine through it on his birthday. Parker says that though many megalithic remains refer to the sun or moon, speculation as to the significance of this is only that: “The reasons for solar alignments can be far from profound.”

The motives of ley line hunters are clear. They believe the country is bisected by great lines of spiritual energy, which pools in certain places, emitting benevolent power. Discovering and seeing where these lines take them is the business of the ley hunter.

The Belinus Line runs from Inverhope on the tip of Scotland to Lee on Solent. It intersects with the St Michael Line, which runs from the end of Cornwall, via Glastonbury and Bury St Edmunds to the Norfolk coast at Hopton-on-Sea.

The implications for people residing on leys are unclear, though an astrologer with an intersection in his Yorkshire garden claims it energises him, “the psychic equivalent of a large Scotch”. Leys were invented, or discovered, by Alfred Wallace in 1921. Wallace thought they were ancient trade routes. When it was suggested that they made odd paths, running through difficult ground and over cliffs, he asserted that our ancestors were more dauntless than us. Ley hunting’s leap forward came in 1969 with the publication of John Michell’s bestseller The View Over Atlantis. Ley lines are currents of terrestrial magnetism, Michell believed, providing “the spiritual irrigation of the countryside”. Stone circles, Victorian churches, Roman remains and medieval castles all aligned on leys, akin to “dragon lines” identified by Chinese devotees of feng shui.

Beside this dose of psychic geography, Parker’s chapters on canals and pilots’ maps seem very grounded. Britain’s aeronautical capital is Farnborough, where a resin-preserved tree commemorates Samuel Cody’s Army Aeroplane No 1, the power of which he tested by harnessing it to the tree in 1908. He flew 424 metres, making Farnborough Common the first runway in Britain.

Our first stratospheric balloon ascent was made in 1862 over Wolverhampton. James Glaisher and Henry Coxwell went six miles up. Glaisher blacked out but a frostbitten Coxwell got them down into a field near Ludlow. Parker talks to private pilots who see a small country (Blackpool is visible from over Guernsey) with a diminishing sky. They complain that controlled commercial airspace consumes more of their freedom annually. Canal enthusiasts are comparatively optimistic. Volunteers work on reopening and preserving them: we now have 3,000 miles of “shimmering ribbons”, as Parker has it, tying the North Sea to the Irish Sea, “enough to provide a smooth, watery highway from London to Casablanca”.

In her Afterword Parker admits that maps of British networks of nuclear shelters (Corsham in the Cotswolds has a 35-acre giant, fit for 4,000), telecommunications cables or Arthurian sites might all have provided chapters. “Wherever you live, you are at the centre of somebody’s Britain,” she writes, and says she hopes to inspire exploration. I hope she continues hers, and publishes more. At twice the length this book would have been no less enjoyable.

Britannia Obscura: Mapping Hidden Britain by Joanne Parker